The Kennet Valley Storage Reservoir of 1893

In the 1890s a proposal was put forward to create an enormous reservoir that would have engulfed Aldermaston and significantly changed the Kennet Valley.

Background

London was the largest city in the world in the nineteenth century, attracting people from rural areas and overseas. Alongside the population growth came pressure on resources. This was the era of Bazalgette’s sewer system and Sir John Snow’s work on epidemics, so there was a growing recognition of the role that clean water and waste treatment could play in reducing some infectious diseases. Anticipating further population growth, the authorities wanted to be able to secure adequate water supplies to the city throughout the year.

In 1892 a “Royal Commission on Metropolitan Water Supply” was set up, with Lord Balfour of Burleigh as its chair. The terms of reference focused on the Thames and Lea rivers, but were broad enough to cover any other ideas that contributors may have. During 1892 and 1893 the Commission heard from several parties, one of whom was Henry Robinson.

Professor Robinson’s Proposal

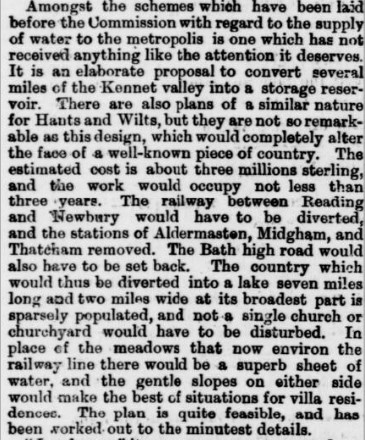

Henry Robinson was Professor of Civil Engineering at Kings College and had been President of the Society of Engineers in 1887. He ran his own civil engineering practice in London and had previously carried out several important projects across a variety of areas, including hydraulic power, electrical lighting, water supply, sewerage and railways. Professor Robinson told the Commission that there was a valley to the west of Reading whose river flowed into the Thames and he proposed “appropriating” this valley for an enormous reservoir. The water wouldn’t be piped directly to London, but instead used to top-up the Thames flow, taking into account a potential future population of 10m people in London.

“The land to be submerged is singularly free from buildings. There are no churches or graveyards within the area, and only two villages would be interfered with,—Aldermaston and Woolhampton. The population disturbed would be 500 or 600”

The Kennet Valley Storage Reservoir

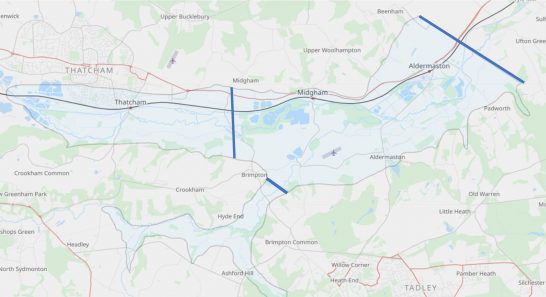

The main dam of the reservoir would have been centred around Towney Lock, running perpendicular to the A4 at the Shell Garage for 1.75 miles and carrying a public road from the (redirected) Bath Road. It would have had a height of 37 metres. The reservoir would have extended approximately 8 miles to near the Nature Discovery Centre in Thatcham.

An upper bank would have been roughly where the Brimpton Road is, and would have been shorter at a mile in length, but 20 metres across, carrying a road. A third bank, the “Enborne Bank”, was shorter still at half a mile, but would have been 40 metres across. This was to carry the K&A Canal, which at this time was still operational (albeit not prosperous), which would have been diverted up a series of locks near Ufton, passing Padworth and Aldermaston, crossing the Enborne Bank and continuing alongside the new lake, joining the existing canal at Newbury. The railway and Bath Road would also have been diverted along the northern shore of the lake, although it is questionable whether all three stations would have been rebuilt, given the reduction in local population.

In Aldermaston Village, the Hinds Head pub is 59m above sea level. The surface of the lake would have been 72m above sea level, so all of the residential and farming part of the village would have been submerged. St Mary’s Church (as noted previously by Professor Robinson) and Aldermaston Court would have been safe, as they occupy the high ground, as do other churches and manor houses in the area affected,

One important local feature for the engineers was the well at Aldermaston Brewery. At the time the geology of the valley was uncertain. The proposers insisted that there were widespread London Clay deposits and at a sufficient depth to ensure that the reservoir would be water-tight. One of their sample sites was at the well, but they lacked other sites to support their assertion.

The Enborne branch would have spread in two directions. The eastern arm would have gone over the Ship Inn, whilst the western arm would have continued to near the edge of Crookham Common. Interestingly, there were later plans for an Enborne Storage Reservoir, which would have been deeper and therefore extended further back along the valley, flooding Headley and reaching the Swan in Newtown. Plans in 1948 were discussed in Parliament and were the subject of significant local protests and there was an unsuccessful attempt to revive them as recently as 1976.

Scale of the plans

The total proposed volume would have been 44,000 million gallons = 200 million cubic metres = 80,000 Olympic sized swimming pools. The current largest artificial lake in the UK is Kielder Water, completed in 1982, which is a similar size. In the context of 1893, the recently completed Lake Vyrnwy reservoir in North Wales was the largest artificial body of water in the country – the Kennet Valley Scheme would have been more than three times the volume.

Outcome

It will come as little surprise to hear that the scheme didn’t go ahead and the villages of Aldermaston and Woolhampton didn’t end up as curious features at the bottom of an enormous lake. The Commission delivered its 84 page report covering all proposals. The Kennet scheme was praised for its ambition, but the geology was seen as unproven and the £3m cost prohibitive for such a risk. Instead a series of smaller projects were carried out, including building the Staines Reservoirs (completed 1902), increasing extraction from Kent sources and starting to build a series of reservoirs in the Lee Valley.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page